Michael Maloney explains, “We were aiming to develop an amplifier that was well manufactured.” “When we started in the late 1970s, the quality of the components was fairly bad. In the signal path, they were still utilizing ancient carbon resistors and electrolytic capacitors, and the printed circuit boards were still Bakelite. We were among the first to employ 1% metal film resistors, and we used gorgeous capacitors made of polypropylene and polystyrene. We didn’t have any mica capacitors in it, but we did have glass-fiber printed circuit boards and the latest Japanese transistors, including the first MOSFETs, which were paraded as valve replacements…”

Myst was the company, and he was a young man who adored music. Rather than the standard variant on the theme of electronics that so many audio industry figures invariably read, he had recently graduated from university with a degree in Perceptual Neuropsychology. He was an expert in electronics, but his lack of formal education led him to believe that electronic components had their own auditory signatures, which he was correct about. The design and execution of the new tma3, which sounded dramatically better than most rivals at or near its £250 retail price, represented such groundbreaking thinking.

Michael preached and practiced minimalism – less frills on the outside of the amp and greater engineering on the inside. Only the power switch, volume control knob, and source selection buttons were present on the tma3. “I remember seeing a hi-fi magazine when I was a child, and on the front was an Italian amplifier called the Galactron, and on the back panel there must have been upwards of a hundred phono sockets, and that got me going,” Maloney says. Because I believe that this is completely needless. All we want is something to listen to albums on. We don’t need all of these dials and connections; all we need is a simple input and output, and to make it well, to make it attractive, and to make it last. And that was the beginning of my desire to pursue a career in audio. That sat at the back of my mind for ten years.”

Michael went to work with Chum Kersting in Norwood after graduating from the University of St. Andrews, where he made some of the “leading” valve amplifier output transformers of the period. He was very interested in learning how to do this since he wanted to build his own valve amplifier. Indeed, the Stage-Life, Myst’s first product, did exactly that. Unfortunately, Chum suffered a stroke, and Michael founded Myst with his partner Mary Guillaume just around the corner from his Norwood company. “We needed a factory to work in,” he explained, “and the Welsh Development Agency was offering residences and factories in their new town in mid-Wales, which they had surprisingly named Newtown.” And Laura Ashley was one of their early triumphs; anyone could rent a house and a factory at a very low monthly rent, so we decided to take a look.” They did, but they didn’t enjoy it, so they drove back to London via Herefordshire, where they were completely enchanted. “Mary and I both said to ourselves, “That’s where we want to live!”

The pair eventually settled in Weobley, where they – and Myst Ltd. – still reside. “It was just big enough for a lovely listening room with blue velvet drapes and a big brick pillar that I erected to house all the gear.” Then there were two rooms in the rear where we could build equipment, so we hired two females from the village to come in and put things together, and that was the beginnings of Myst. We adore being here; it’s fantastic. It’s completely useless for anything involving world dominance or thinking about world dominance. “The rest of the industry went to Huntingdon and Cambridge, and we ended ourselves here in Herefordshire, in the area that time forgot,” Michael confides.

The new integrated amplifier was produced in a newly built factory and office facility near the Brecon Beacons, and it was touted as “not merely another budget amplifier.” Michael is a little vague about why it’s called ‘tma3,’ first suggesting that it stands for “the Myst amplifier no.3,” then admitting that he’s a big fan of Arthur C. Clarke and suggesting that it could be a reference to his “tyco magnetic anomalies,” where the Monoliths are discovered in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Whatever the case, the new amplifier appeared to be extraterrestrial at the moment. “The squares of the first three prime integers gave it a dimension of one-to-three-to-nine. Michael tells me that they were the measurements of the monoliths in Arthur Clarke’s 2001 book…

Still, if you thought the Myst integrated was artistically or thematically out of the ordinary, wait until you see what came before it. The Myst G-Ohm pre/power amplifier had a good reputation for sound, but it didn’t win any awards for ease of use or modern style — and what was with the name? The general caliber of the materials, circuit design, and components was top-notch considering the price, and everything was obviously very lovingly put together in all Myst products. It wasn’t all about showing off the ‘perceived’ cost of the product; rather, the general caliber of the materials, circuit design, and components was top-notch considering the price, and everything was obviously very lovingly put together in all Myst products. The tma3 was essentially a smaller, more compact G-Ohm with a less extravagant power supply (432x220x55mm).

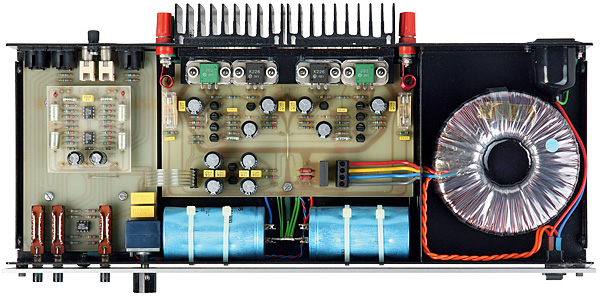

The Myst integrated is a gorgeous item to look at on the inside. Back in 1983, the average Japanese amplifier – and many British ones as well – was a jumble of cabling, with a slew of sub-boards strewn around and the standard frame-type power transformer. The Myst, on the other hand, paid close attention to earthing, being star-earthed long before it was fashionable. The communication pathways were kept short and the wiring was clean. A massive, high-quality toroidal mains transformer provided power, with separate power rails for the preamplifier and power amplifier units.

The more you looked into the tma3, the more loving attention to detail you noticed. A high-quality ALPS potentiometer was used to control the volume, which was compliantly attached to reduce mechanical vibration. The phono card (MM or MC) included excellent 1 percent tolerance polystyrene capacitors and metal film resistors, while the circuitboards were carefully put out high-quality things. High-quality polycarbonate capacitors were used to connect the preamp to the power amp, and the power amp itself was based on a classic Hitachi design with just five transistors and Hitachi 2SK226/2SJ82 MOSFET output devices, which were connected to the loudspeakers through a 2.5 amp quick-blow fuse. The quality was excellent, as was the dependability. “No one has ever called me and said you sold me a piece of crap that is nothing but hassle,” Maloney adds.

The manufacturer stated a power output of 35W RMS per channel into 8 ohms, which sounds tiny now but was quite powerful in the early 1980s. It wasn’t bad, especially considering that Naim’s NAIT integrated, which debuted about the same time, barely managed to make 20W. However, another new similarly priced amplifier, Audiolab’s 8000A, came at the same time and put out 50W RMS into 8 ohms, making it a real powerhouse. Despite its small size and mediocre rated power, the Myst came across in real life as a robust and gutsy performer; there was definitely a sense that it was competent at current driving when called upon to do so…

“The Quad ESL-63s were the best sounding loudspeakers of the period, by a mile,” Michael Maloney says. The tma3 had the MOSFETs, the best power supply, and the large toroidal transformer to drive Quad Electrostatics the way they were supposed to be driven. They were half the price of a house back then, so I don’t think many people bought tma3s to drive Quads back then, maybe a handful. We used the Celestion SL6 as a reference, and the tma3 and it worked perfectly together. It was a difficult speaker to drive, but Celestion saw the amp and asked us to work on an active version of the SL6. It was always a skunkworks project, not a production. We had one power amp driving both drivers, one for the woofer and one for the tweeter – and it was stunning, the bee’s knees!”

The Myst tma3 still sounds great in action. It’s a powerful little integrated that easily outperforms its 35W per channel rating (50W per side would be more appropriate) and excels at driving modest loads. With a damping factor of 110, it has a firm hold on loudspeaker bass cones, and everything else is clean and exceptionally detailed, with excellent soundstaging. It is never analytical, though, and has true musical coherence, making it a joy to listen to in its own right, quiet, measured, and precise. The phono stage is excellent, and back in the day, a variety of MM or MC plug-in cards were available. Surprisingly, the CD input bypasses the preamp portion and instead goes straight to the volume control and power amp, which sounds fantastic.

Myst was an oddball corporation, and you had to admire the hilarity that surrounded it. The original Stage-Life valve amplifier, introduced in 1981, was available in two brown hues. The brown and champagne gold color scheme of the 1982 G-Ohm (perhaps an acronym of Mary’s surname?) appeared. The tma3 arrived a year later in silver and blue, though an all-black option was available, and most tma3s were sold in this livery — for which you’d have to add roughly £25 to the purchase price. If the dimensions of the tma3 look particularly familiar, you may have owned a pair of Celestion SL6s — the amp’s casework is identical to the sand-filled metal uprights in the SL6 stands; in fact, the latter was inspired by the former! The Wellard loudspeaker, a superb mid-sized studio monitor that Myst sold to the great and the good of the British music scene in the mid-to-late 1980s, is the best Myst legend. Everyone from Phil Collins to Stock, Aitken, and Waterman purchased a pair, and it was this that propelled the company away from the domestic hi-fi market.

Overall, this is a fantastic, long-lost integrated amplifier from one of Britain’s most iconic ‘cottage industry’ firms. We wish Myst the best of luck, and who knows, maybe they’ll return to making fantastic hi-fi in the future?