The vintage Ultimo 10X, a high output moving coil built and manufactured by Dynavector of Japan, will be remembered by any analogue enthusiast worth his record collection. It was one of the most musical cheap pickups available in the late 1970s, with the added benefit of not requiring a pricey step up transformer. The problem was that pukka moving coils had to have low output for many people back then, otherwise they weren’t The Real McCoy. This made sense because most attempts at high-output designs failed because higher output voltages generally resulted in acoustically costly compromises and/or tracking difficulties.

The exception that proved the rule was Dynavector. Professor Noburu Tominara of Tokyo University, the company’s creator, was a world expert in tiny coil winding technology. He created a winding machine that employed ultra fine wire and had the best output-to-mass ratio in the industry. It has been crucial to Dynavector’s success to this day. Of course, employing a large amount of wire to obtain a high output compromises performance, but it also eliminates a potentially more major stumbling block later in the replay chain: the active moving coil phono stage.

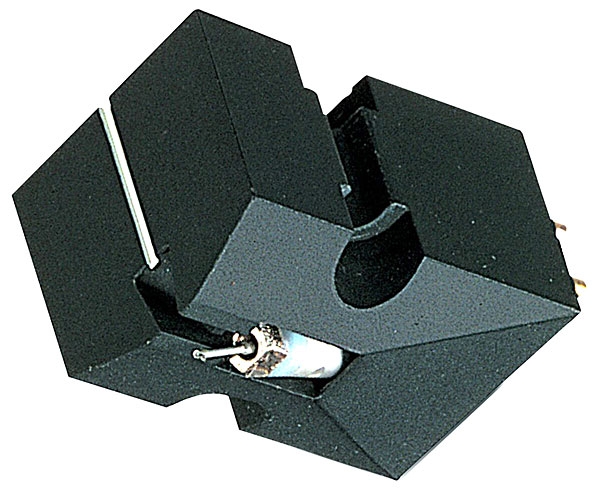

The problem is that good moving coil phono preamps are complicated beasts that cost a lot of money to build correctly. Although a mid-price integrated might offer an MC facility, it’s unlikely to be up to the task, so why not opt for a good high-output moving coil instead? Put another way, even before you take it out of the box, the DV-20X H makes a strong argument for itself. The body is made of machined aluminium alloy, and the cantilever is made of strong aluminium pipe and fitted with an elliptical naked diamond stylus. The Dynavector tracked quite well at the bottom of its 1.8-2.2g range in a Michell Orbe/Origin Live RB250, and its 8.6g total mass was no problem for the Rega counterweight.

It struck me right away how different it was from most moving coils as soon as its stylus reached the groove. Audio-Technicas have always had a thrilling sound, but they may be tonally thin and harsh, whilst Ortofons are more refined, but can be bland at times (or dare I say it, Scandinavian). The Dynavector, on the other hand, walks a fine line between these two extremes. It produces a deep, rich melodic sound that we all enjoy; in fact, it performs all of the functions of a good moving magnet, but better. Then it begins to do all of the wonderful things that moving coils are known for, such as crisp, clean treble, excellent soundstaging, tight imaging, and true dynamics.

The Crusaders’ Street Life, for example, began with a powerful Randy Crawford echoing between my speakers. Her voice was thrust favourably forward into the room by the DV-20X H, which also dragged the accompanying keyboards back. The saxophones were gloriously deep and breathy, and the drum kit was very tight and delightfully aggressive. An uncharacteristically direct and unafraid performance. The Dynavector was even better when it came to The Prodigy’s One Love. It boogied and got into the flow of the music. The imagery was unusually huge and vivid, the bass kicked like it was going out of style, and the frenzied percussion thumped like a crazed thing from the mix. It’s a lot of fun, and it’s not too dissimilar to the old Decca London Export.

Jazz was also a treat thanks to the DV20’s ability to follow the beat, as well as its succulently rich, velvety tone. The Dynavector was perhaps least successful in classical music. It wasn’t horrible, but it seemed a little too colorful and unsubtle to resolve every every nuance of an orchestra in the way that more costly coils do. There’s a lot of low-level detail and precision missing, as well as a true three-dimensional soundstage, in absolute terms. Overall, this is a really good cartridge for the price, which was £295 when it was initially released. Don’t assume Dynavectors aren’t good just because they’re a mystery in the UK — the DV20X-H Black proves otherwise.