Vinyl began declining in popularity in the early 1990s. It had a ‘end of the century’ vibe to it, as if the sting of death will befall it soon long. As a result, the availability of low-cost, high-quality cartridges began to dwindle. The Ortofon VMS series was silently being phased out of dealers’ inventory lists, Audio-range Technica’s was not being updated, and Shure appeared to have given up on the non-DJ market. Goldring’s 1000 series arrived just in time, providing much-needed relief to those of us who were still interested in the ancient format.

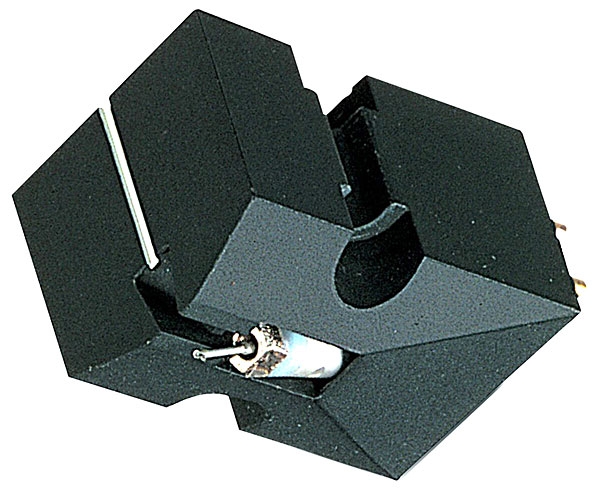

In 1995, the Goldring 1042 was released for the princely price of £90. This wasn’t a rehash of an old design; it was a brand-new product based on audiophile best practices. It was fantastic when mounted in an excellent mid-priced arm like Rega’s ubiquitous RB300. Despite being the flagship of the British business’s moving magnet range, all other models used the same glass-reinforced polyester body (dubbed POCAN by the manufacturer). This material was less resonant than earlier generations of cartridges’ metal bodies, yet it was just as robust.

The stylus was the only difference between it and the cheaper models, which shared a new neodymium magnet assembly and wiring. It employed a Fritz Gyger-S extended groove contact design from Switzerland. It’s a pricey tip that you won’t find on most mid-price cartridge designs, especially ones with moving magnets. When compared to the base model 1006, it significantly improved fine detail resolution, smoothness, and polish.

The end result was a sound that combined the advantages of the 1000-series chassis – a big, powerful, musical sound with a punchy 0.65mV output that flattered inferior MM phono stages – with the finesse you’d expect from a moving coil. To put it another way, the 1042 tried to combine the best of both worlds at a low cost. In this regard, it was a direct competitor with the Dynavector DV10X4 high output moving coil, and they ended up sounding quite similar in certain ways; if anything, the Dynavector was the less complex but more feisty performer.

The frequency response of the 1042 was very flat, ranging from 20Hz to 20kHz (-3dB), however the bass was a touch plumper than the treble. For many, this was a welcome reprieve, as loudspeakers in the 1990s were notoriously bright, and the Goldring was an excellent palliative solution. It had a powerful left-to-right image with big brushstrokes, resulting in a positive and confident recorded acoustic. It lacked fine resolution and was not as good as more expensive moving coils in terms of depth perspective (it tended to hang instruments about the plane of the speakers).

The 1042’s drawback is that it just provides you a taste of the good life, leaving you wanting more. Yes, it’s rather detailed and rhythmically engaging, but you can’t help but want for a sharper, more atmospheric treble and a tauter, tighter bass. It sounds like a cartridge version of an excellent KT88 valve amp in terms of punch and enjoyment, but it’s a little opaque.

It’s an easy partner for most middle mass modern arms, with compliance of 24mm/N (lateral) and 16mm/N (vertical), and it’s nothing exceptional electrically, either, with a load of 47K ohm and 150-200pF. That’s the beauty of the 1042: it’s simple to use and compatible with a variety of accessories. Its 6.3g weight is easy to balance, and its 1.75g track is quite secure. Of course, the stylus assembly can be replaced, but at £185, it’s becoming pricey. The 1042 now costs £285 new after two decades. Even so, it’s still an excellent buy — think of it as your last moving magnet cartridge; after that, you’ll need a £500-£1,000 moving coil.